My Experience

While everyone must choose what works best for them, I have embraced a plant-based diet and experienced remarkable health benefits, despite a family history of heart disease and aneurysms on one side. I have outlived half of my cousins and siblings, even as the oldest sibling. Growing up, I suffered from colic, chronic sinus congestion, severe acne, and daily stomach aches—all of which disappeared after I eliminated dairy from my diet. My good health may also be partly due to prioritizing organic foods, which help reduce food allergies. My passion for vegetarian nutrition and environmental issues led me to conduct research in this field. You can find my diet-related journal publication listed in the references.

Your Choices

Prefer Low Impact Foods

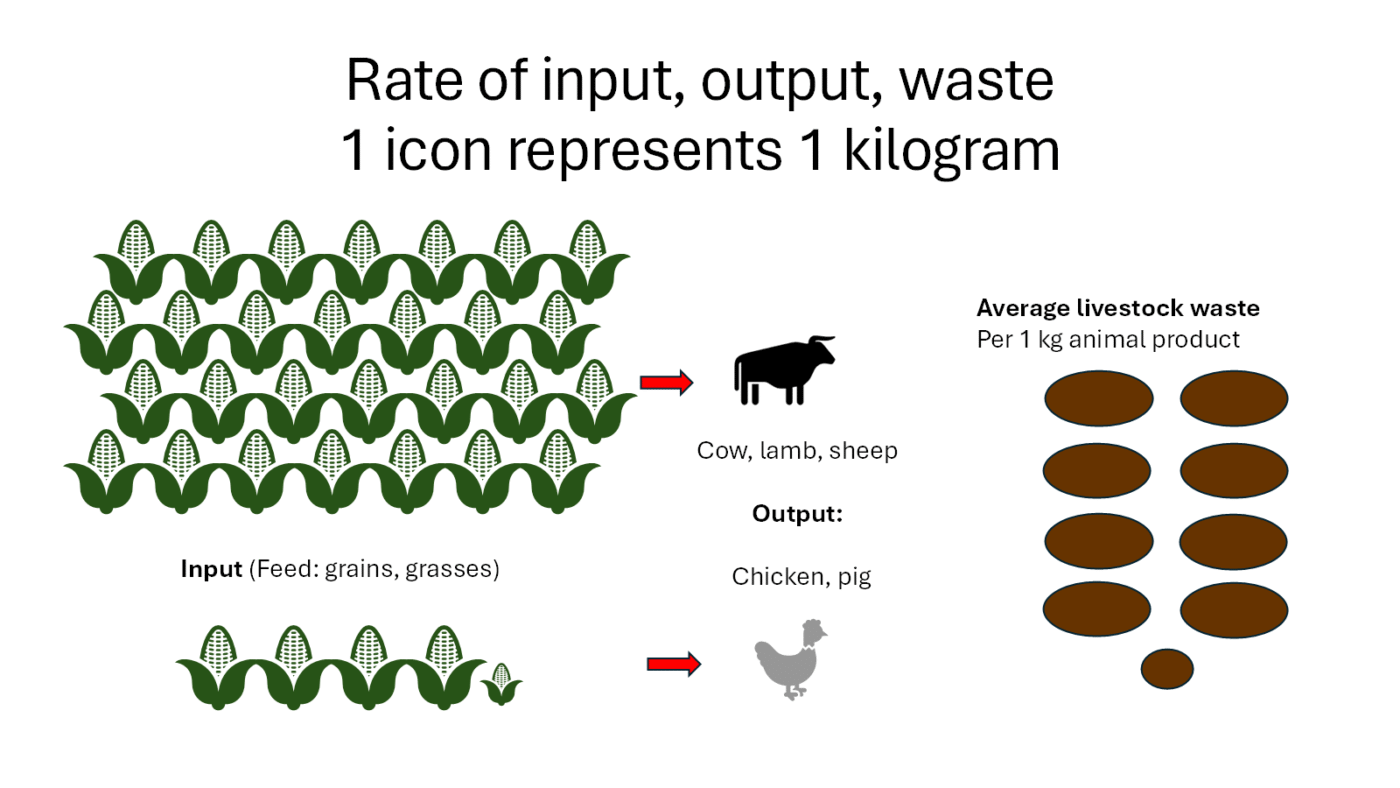

Animal agriculture has been described as ‘factories in reverse’: it requires a great deal of feed to produce a small amount of food, especially with beef and dairy. Much of the corn grown in the U.S. Midwest is used to feed livestock, not people. Globally, all grazing lands and 63.8% of crop production support animal agriculture, while only 36.2% of crops are grown directly for human consumption (UN IPCC, 2014). Beyond environmental concerns, switching to a plant-based diet offers numerous health benefits. This webpage explores the environmental impact of meat consumption, the advantages of plant-based eating, practical tips for adopting a more plant-based diet, and the scientific evidence supporting these claims.

The diagram above illustrates that producing 1 kg of beef, lamb, or sheep meat requires 28 kg of input feed such as corn and soy, with beef generally demanding the most. In contrast, chickens and pigs are more efficient, averaging only 4.3 kg of feed per kilogram of meat, with chickens being more efficient between the two. Additionally, livestock generate an average of 8.38 kg of waste, including manure, urine, and dead animals (from weak or diseased animals), for every kilogram of meat produced. This data is sourced from the UN IPCC (2014, p. 836) and further discussed in The Science: Why Meat is Problematic. In contrast, if you eat grains (e.g., corn, wheat, quinoa, rice) and legumes (e.g., lentils, tofu, beans, peas) directly, then 1 kg of farm produce is directly 1 kg of food to you.

This inefficiency has significant environmental implications (FAO, 2023):

- The amount of fertilizer required for meat is several times the fertilizer required for plant consumption. Fertilizers include carbon and nitrates, which result in greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide. These substances also contribute to ocean acidification and eutrophication, leading to the degradation of lakes and bays.

- The amount of pesticides and herbicides required for meat is multiple times the chemicals required for plant consumption. This leads to more toxic fields and waterways, harming wildlife as well as potentially contaminating our drinking water. Certain chemicals have been linked to higher risks of cancer and Parkinson’s disease.

- The amount of water required to produce meat is much greater than the water required for plant consumption. Consequently this leads to regular drilling of deeper wells in arid regions.

- Increased land use leads to fewer forests and natural grasslands. Trees purify air, cool neighborhoods through shade, produce fruits and nuts, absorb carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas), and help manage flood waters. Natural forests and grasslands sequester carbon in their plants and soil more effectively than grazing lands. Additionally, these ecosystems offer vital habitat and food sources for wildlife.

- Cows, sheep and goats generate greenhouse gases through a digestive process, known as ruminant enteric fermentation, which accounts for a significant portion of livestock-related emissions. Additionally, manure releases methane and nitrous oxide, further contributing to greenhouse gas production.

Eat Less Meat (Particularly High-Impact)

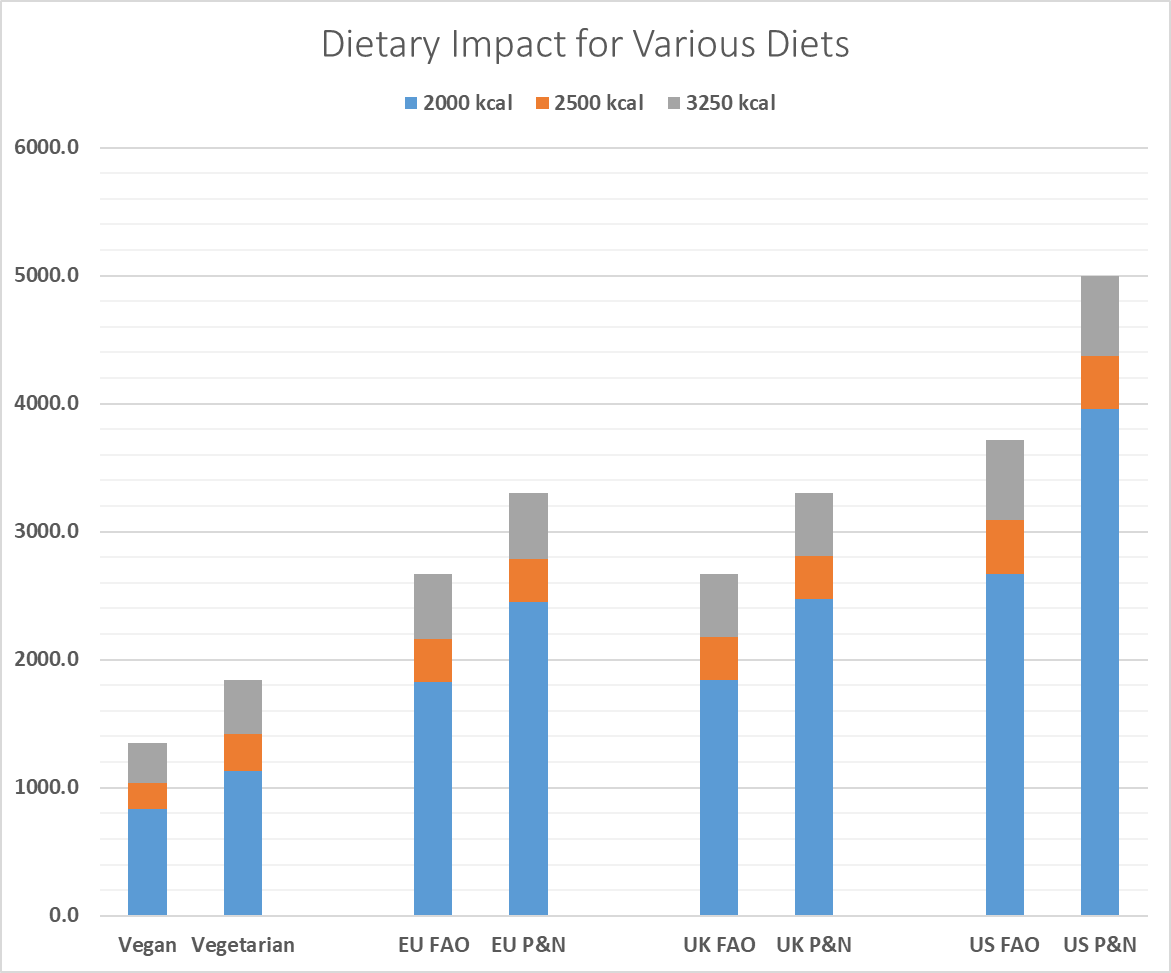

The figure above illustrates the significant impact of diet on greenhouse gas emissions, based on 2023 data recalculated from Lincke & Wolf (2023). We present findings from the traditionally accepted United Nations FAO report (Gerber et al., 2013) alongside more recent research by Poore and Nemecek (2018), cited by Statista and Our World in Data. However, even the Poore and Nemecek results are conservative; the section The Science: How Meat Is Problematic outlines additional factors not accounted for.

The average American consumes 278 grams of meat per day (excluding fish), while the average European consumes 195 grams (Lincke & Wolf, 2023). For context, a quarter-pounder burger weighs 112 grams. A lower-impact vegan diet consists entirely of plant-based foods, with vegetarians including eggs and dairy cheese. Note that the typical American diet results in approximately 5 tons (5000 kg) of greenhouse gas emissions annually, whereas a vegan diet produces less than 1.5 tons, with many variations in between.

The bar chart illustrates three consistent calorie values for each diet: (blue) 2000 kcal representing the recommended intake, (red) 2500 kcal commonly reflecting actual consumption, and (gray) 3250 kcal including food wasted at home and in stores. By minimizing food waste in stores and homes, we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 30%, equivalent to about half a ton. Additionally, reducing meat and dairy consumption can lower emissions by 1 to 4 tons, depending on the specific foods replaced.

Foods that produce low greenhouse gas emissions generally score low across all environmental measures, including water use, land use, water pollution, erosion, and eutrophication. Clark and Tilman (2017) found in their study: “Indeed, for all indicators examined, ruminant meat (beef, goat and lamb/mutton) had impacts 20–100 times those of plants while milk, eggs, pork, poultry, and seafood had impacts 2–25 times higher than plants per kilocalorie of food produced.” For detailed impacts of specific foods, visit Environmental Impacts of Food Production – Our World in Data.

To estimate your personal greenhouse gas emissions from your diet, visit Calculate Your Footprint and use the Diet page. It customizes the results based on your individual dietary choices.

Isn’t meat necessary? What about Protein?

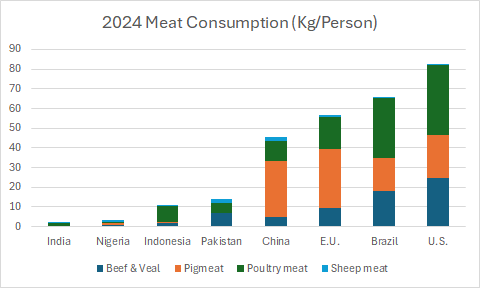

Most of the calories we require are for maintaining energy and supporting metabolism, while protein plays a crucial role in rebuilding cells. Although protein is essential for good health, consuming meat is not necessary. The graph below illustrates the average meat consumption in the eight most populous countries in the world. As shown, many populations thrive with significantly lower meat consumption compared to others. This data is sourced from the OECD database (2024).

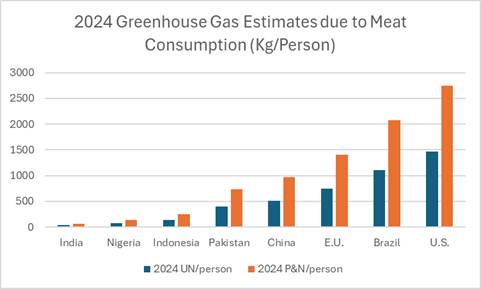

High meat consumption significantly increases per-person greenhouse gas emissions attributed to meat. The blue bars in the graph below represent UN-calculated statistics, while the red bars reflect recent research by Poore & Nemecek (2018). For example, the European Union’s meat consumption alone is estimated to produce between 1 and 2 tons of greenhouse gases per person annually (UN FAO = 1000 kg = 1 ton; Poore & Nemecek = 2000 kg = 2 tons). In the U.S., emissions range from 1.5 to over 2.75 tons per person each year. In contrast, countries like Indonesia, India, and Nigeria generate at or below a quarter ton of greenhouse gases per person from meat consumption.

Plant-based sources of protein with much lower greenhouse gas impacts include lentils, peas, beans, various nuts, soy, tofu, tempeh, and seitan. Additionally, all whole foods, including vegetables and whole grains, contain protein. This graph reflects conservative estimates; for a more detailed and accurate analysis, see The Science: Why Meat is Problematic.

Add Healthy Plant-Based Foods

Health Benefits for You: Adopting a sustainable, whole-foods diet can enhance your overall health, support weight loss, and lower the risk of many chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, and diabetes (Greger, 2016). Plant-based diets have demonstrated the ability to reverse conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, kidney disease, and diabetes. They also help reduce the risk of strokes, Alzheimer’s, and specific cancers like breast, prostate, digestive, and blood cancers (Greger, 2015). A diet abundant in fruits and vegetables may also alleviate symptoms and decrease the risk of asthma, COPD, lung cancer, prostate cancer, and Parkinson’s disease.

For more detailed guidance on preventing and potentially treating these diseases naturally, Michael Greger’s How Not to Die. His book How Not to Diet offers evidence-based strategies for effective weight loss on a plant-based diet. Both books are extensively researched, with approximately one-third of their content supported by scientific studies.

The best way to implement a plant-based diet is to emphasize whole foods, emphasizing the four plant-based food groups (PCRM, 2024):

- Vegetables: including cruciferous varieties such as broccoli, bok choy, cabbage, kale, and arugula; other salad and leafy greens; root and tuber vegetables; asparagus; squash; peppers; mushrooms and sea vegetables.

- Protein: lentils/peas, nuts, beans, seeds like sunflower, sesame, tofu, tempeh, seitan (also known as wheat meat).

- Grains: rice, corn, quinoa, oats, buckwheat, whole wheat, faro, barley, teff, rye, Grains provide both energy and plant-based protein.

- Fruit: berries, melons, apples/pears/peaches, citrus, grapes, bananas, avocado, mango, and more.

Most plant-based foods are rich in fiber, which helps lower cholesterol and reduce the risk of heart disease. For additional guidance on adopting a plant-based diet, see the Plant-Based Eatwell Guide: https://plantbasedhealthprofessionals.com/wp-content/uploads/Plant-Basted-Eatwell-Guide-A4.pdf.

Beginning with familiar foods like lentil or bean soups, vegetable stir-fries, and potato or whole-grain pancakes (such as oat or buckwheat) can be an excellent way to transition to a more plant-based diet. For inspiration and ideas on creating a lower-impact and healthier menu, see “What’s for Dinner?”

An essential nutrient for plant-based diets is vitamin B12. B12 is produced by bacteria and can be washed away when vegetables are cleaned. Cows obtain enough B12 by eating unwashed grasses, which is why meat-based diets often provide sufficient B12. However, diets high in meat often lead to increased fat and cholesterol intake, which can contribute to high blood pressure and the need for medication. Ultimately, the choice comes down to supplementing with B12 or managing high blood pressure with medication. B12 supplements are more affordable, natural, and free from negative health effects.

References

Michael Clark and David Tilman (2017) Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 (2017) 064016, IOP Publishing.

FAO (2023) The State of Food and Agriculture 2023 – Revealing the true cost of food to transform agrifood systems. Rome.

https://doi.org/10.4060/cc7724en

Gerber PJ, Steinfeld H, Henderson B, Mottet A, Opio C, Dijkman J, et al. Tackling climate change through livestock. Rome: Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations (FAO); 2013.

R Goodland and J Anhang (2009) Livestock and Climate Change: What if the key actors in climate change are… cows, pigs, and chickens? World Watch, Worldwatch Institute.

Greger, M., & Stone, G. (2016). How Not To Die. Macmillan.

M Herrero, S Wirsenius, B Henderson, C Rigolot, P Thornton, P Havl´ık, I de Boer, and P. J. Gerber (2015) Livestock and the Environment: What Have We Learned in the Past Decade? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2015. 40:177–202.

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment

Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K.

Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C.

Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Lincke, S. & Wolf, J. (2023). Dietary modeling of greenhouse gases using OECD meat consumption/retail availability estimates. International Journal of Food Engineering, 19(1-2), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijfe-2021-0352

OECD (2024). OECD Data Explorer. From: https://data-explorer.oecd.org.

PCRM (2024). Protein: Power Up with Plant-Based Protein. Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. From: https://www.pcrm.org/good-nutrition/nutrition-information/protein.

J. Poore and T. Nemecek.(2018) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. SCIENCE, 1 June 2018, 360(6392) 987-992. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

G Wedderburn-Bisshop (2024) Consistent, Inclusive Emissions Accounting Identifies Agriculture as the Leading Cause of Climate Change.